Project Technical

|

|

Recap from

|

Our research team has explored how citizens (and the spaces we call the city) play with language and literacies. We have learned that still calling cities monolingual (Mora et al, 2018) ignores how citizens really use the multiple languages hiding and (re)surfacing in our cities. We have also learned that sustaining such traditional visions of what makes a city “multilingual” does a disservice to the city and its dwellers, as these visions sometimes gravitate to causalities that keep linking language and literacy command to socioeconomic status. As we learn more about how multiple languages intersect with daily lives, we have learned that literacy practices in the multiple languages and forms of meaning-making available are no longer just individual moments. Instead, we keep discovering different socially-constructed narratives where (in the case of non-Anglo countries such as ours) English is one part of a more layered, uneven, and more complex community-building tapestry than traditional research seems to be aware of.

|

Situating

|

As second languages are part of everyday lives, we need to interrogate how these communities appear, develop, and grow within our cities and understand the educational and social implications of these events. Aligning with this year’s conference theme, we are in the middle of a worldwide turn of the tide. Inspired by the recent demands for Black linguistic justice (Baker-Bell, 2020; Baker-Bell, Williams-Farrier, Jackson, Johnson, Kynard. & Murtry, 2020), we believe that calls for linguistic (and literacy) justice also extend to English in places like the Global South. Our research aligns with these calls as part of the effort to move the study of literacy practices beyond traditional knowledge centers (decentering) and so-called standard forms of languages (decentralizing; Mora, et al., 2020). We believe that research about languages in our cities must always reconfigure existing discourses beyond the official norm and we must understand how those language configurations enrich and actually impact our cities and those who make the city living.

|

Our Framework Keeps Expanding |

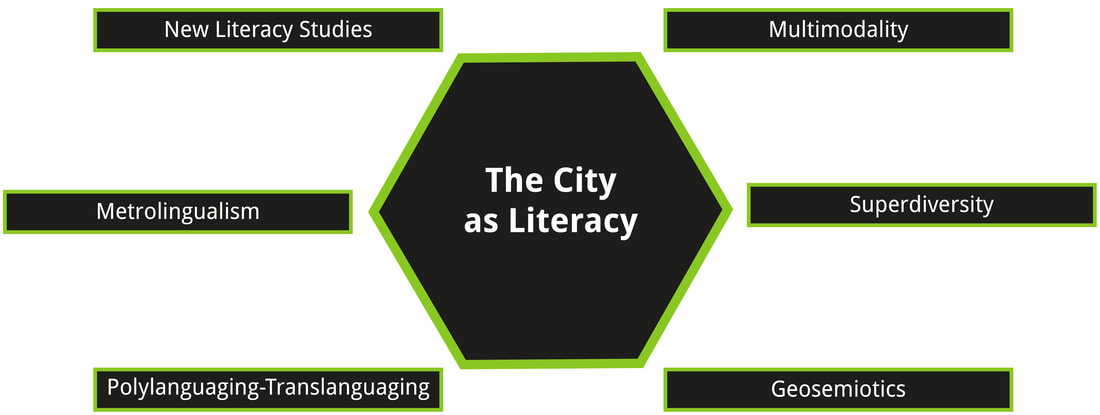

Our entire research inquiry has found inspiration in the New Literacy Studies’ inquiries about the city (Barton & Hamilton, 1998; Gregory & Williams, 2002). We have drawn from this tradition to construct our theoretical framework to understand how “the city (in its condition of nonhuman) redefines the traditional concepts of reading and writing providing new forms of communication and interpretation of the daily interactions with its surroundings” (Author 4 & Author 2, 2020). Our framework to study the city as a literacy practice (Author 1 et al, 2015, 2016, 2018; Author 4 & Author 2, 2020) explores how the city and its citizens coalesce by using languages and literacy practices to reconfigure social relations and even the use of spaces around the city. For this study, we explore the construction of communities through language as meaning-making communicative resources (multimodality - Author 1, 2019; Kress, 2010) linked to other languages in the area (polylanguaging - Jørgensen, 2012; translanguaging - Author 5, 2019; García & Li, 2014). We explore these communities as interconnected (superdiversities - Blommaert & Rampton, 2011) and spread across the city (metrolingualism - Pennycook & Otsuji, 2015; geosemiotics - Author 1, 2016; Nichols, 2014).

|

The City and our Routes as Individual and Collective Narratives |

As we are interested in looking at literacy practices in these community spaces, our team, following the same parameters we defined from our first project, has projected three routes of inquiry, all of them with lead researchers, but under the premise that all researchers are actively engaged in all stages of fieldwork and analysis. The three designated routes are:

|

Academic Presentations

|

2017

|